A selection of the

things I’ve been interested in lately and wanted to share a little

bit about…

Gone Home

Billed as a

first-person exploration game Gone Home, the first game from the

Fullbright Company, is both familiar and unlike any game I’ve

played. Using the familiar techniques honed in dozens of first-person

shooters over the years the game sees you as Kaitlin

Greenbriar, a young woman back

from a year travelling in Europe, she returns home in the middle of

the night to find an empty house and sets about discovering what has

happened in the time she has been away.

From the setup it might sound

like this is a horror game, and despite some very atmospheric

presentation, and the notion of exploring this massive house on your

own at night, that isn’t what the game is about at all. Instead by

exploring the house, uncovering notes, diaries, receipts and clues

you begin to piece together the story of the rest of Katie’s

family, stories that are both sad and true, heartfelt and familiar

and subtly, brilliantly, realised. Her sister Sam is the main focus

of the game and at certain points she narrates dairy entries that

help fill in the blanks. The game is only a few hours long, and

outside of the exploration there isn’t a lot too it, gameplay wise,

but the attention to detail and way in which the family secrets out

themselves to you organically through your exploration make it a

really unique and engaging experience. It’s the sort of game that

is best unspoiled, but if you are interested at all in narrative

techniques in gaming and engaging with smaller, more personal

stories, then Gone Home is well worth checking out.

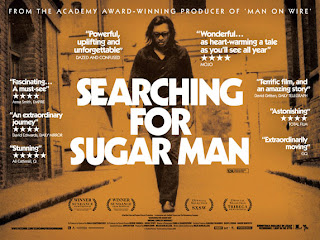

Searching for Sugar Man

Winner of the Oscar for

best Documentary this year, Searching for Sugar Man is one of those

stranger-than-fiction stories that is really best discovered for

yourself. It concerns a small-time musician discovered in Detroit in

the late 1960s and the surprising story of his unknown legacy. I

really don’t want to say more as half the fun of this very

enjoyable film is uncovering the pieces of the puzzle, suffice to say

it’s a journey worth taking and is surprisingly life-affirming as

well.

Fez

Back to games and Fez

was something of a breakout indie hit last year when it was released

on Xbox Live (it was also prominently featured in Indie Game: The

Movie that I reviewed here), with its recent Steam release

though I’ve finally gotten round to playing it, and it is

wonderful. A charming mix of old school 2D platforming with a modern

twist, the fact that you can rotate each world in 3D, turning one 2D

level into 4 separate ones, allowing you access to new areas, doors

and secrets, all in the name of collecting cubes. Wrapped up in it

all though are layers upon layers of secrets, codes and cryptic

puzzles that reveal elements of the game most people probably won’t

find. The game works well enough as a relatively straightforward

platformer, the graphics are great, the levels evocative of the 16bit

era without being beholden to it, combined with the great soundtrack

it makes the world a great place just to explore. But dig a bit

deeper and Fez becomes something else entirely, and even if you need

a bit of a push to uncover some of the extra content, it’s worth it

just to see how far down the rabbit hole goes.

The West Wing

Yes it’s old, but

it’s one of those TV shows that I never watched, for one reason or

another, however now all 7 series are available on LoveFilm I finally

succumbed and found myself watching the first 4 episodes in a row.

Suffice to say I’m enjoying it and I’m sure it only gets better,

but I just wanted to acknowledge the fact I‘m plugging one of the

holes in my TV watching history, and having it all available to

stream and watch whenever I want is wonderful, if dangerous.

So

that’s it for now, not sure if this will become a regular article

or not, may depend on what I find myself enjoying in the future, but

it’s good just to put some thoughts down without the need for a

full article, and to hopefully draw your attention to things that may

be of interest. Normal service (whatever that looks like) should

resume shortly.